Snook is one of the UK 's leading service design organizations.

Ms. Sarah Drummund, the CEO, is one who has been actively engaged in activities since the early beginning of service design in bringing the approach to administration in the UK government.

She also participates in the textbook about service design, "This is Service Design" as an author.

Snook have hundreds of service design projects in the public sector and have created methods of capacity building with continuing persistence over the past ten years.

How does Ms. Drummond capture and practice application of service design in administration?

In this article, we introduce the points of promoting service design within organization, with examples of collaboration between Snook and the government.

Text: Sarah Drummond (Snook / Founder and Director)

Editing: Chikako Masuda

Ten years ago, I sat as the only designer in a Government body asking myself if design would ever reach a critical mass in how our public services are made.

To me, as a trained product designer, the process I knew which focused on putting users at the centre of your design and prototyping ideas before they were finalised seemed to make sense as a recipe for innovation within the public sector. Surely if we took on these basic principles, we’d be able to make public services more usable, meet people’s needs first time and save money in building the right things before costly implementation.

I started my design career in Government at the advent of when people were just starting to talk about design and designers playing a significant role in public sector innovation. At this time, the explosion of digital innovations and possibility had given birth to a whole arena of new services. They made new online transactions possible, but most were very difficult to use and did not think about the user experience in any measure, particularly how on and offline interactions would work together. Often, the service design hadn’t been considered and the user experience was a by-product of developers making an internal system work.

At this time, around 2007, there were little examples of design being applied to Government directly. There were some fringe examples namely Social Innovation Lab Kent (SILK) pioneered by Sophia Parker, an in-house innovation lab in a local authority co-designing services with citizens and the RED unit within the Design Council, considering areas like design for health and transformation around 2006. These projects pointed out that there was a nascent but growing community of practice of designers working in more complex environments with new materials like services and politics but at the time, a lack of designers prepared to work in this space.

Ten years later, the landscape couldn’t be more different.

A decade ago, digital held so much potential and I see it as the vehicle that supported the movement of Service Design to scale within Government, both in the UK and around the globe. As we began to think about more complex interactions, we recognised a need for institutions to really think about the services they offered, how people used them, how their data moved between institutions and interactions became possible across different channels. That’s when I saw the explosion of Service Design happen across Government. Digital changed the Service Design game.

Scaling design across Government

The Government Digital Service, part of the UK Government’s Cabinet Office has been one of the most prolific and tangible developments of design being picked up at scale and embedded across Government. It’s important to recognise there were lots of efforts ongoing before and during GDS but it is the biggest investment in design at its scale in the past ten years. In 2011, GDS were formed to implement the 'Digital by Default' strategy proposed by a report produced for the Cabinet Office with influences from a paper by Martha Lane Fox. Over the past 6 years, GDS has embedded 800 designers across Government and heads of design across the major ministerial bodies. A quick look through the GDS design blog and you’ll see a regular series of posts from designers discussing how services can work better for people at both a macro transformative level (the overall process of moving across Government departments) to the micro interactions (how a font works on screen to be readable across devices) with both being considered in equal measure. Additionally, you’ll see posts by people who didn’t train as designers but have developed skills and the mindset to think like designers due to training that they undertake as civil servants. All of them are discussing how what is being created in Government can meet user needs.

It was obvious to me, that design would be the most obvious choice as a discipline to join the civil service and help make services better. Louis Sullivan, a modernist architect in the 20th century famously coined the term, ‘Form follows Function’ and what better a way to think about making Government work for people but design? When design is finally understood as a creative process of inquiry into how things work over the common outdated understanding that it’s about ‘making things look nice' we know we’re making progress.

When we think about how design can help Government function better, we mean that they do the hard work for users. When you think about a user need to ‘start a business’ it requires a citizen to interface with at least 5 departments, filling in forms, setting up accounts, chasing up paperwork, sending letters. Imagine when we re-design these systems from the perspective of users to make it one simple online interaction how much easier and more cost efficient it would be to run services. It means we stop users from having to be experts of a broken system that wasn’t consciously designed to work for them.

These kinds of user experience shifts require not only front-end user experience to be re-designed by graphic, content, service and interaction designers but also the back end of these services to join up, which is a much larger and complex problem to solve. This means the user experience is everyone’s business, from the legal departments to the teams in charge of data sets per organisation. The front and back end of a service must all work together. This is the totality of service design in Government, and a vehicle like digital does give us the opportunity to question how these outdated systems don’t work together to make experiences work for users.

To do this, GDS built a movement of people adopting a similar mind-set around design. Through a series of basic design principles that have been adapted and copied around the world online and through various ‘Gov Design’ propaganda you’ll find people across Government talking in the same language. From 'start with user needs’ to ‘iterate, then iterate again’ many of the principles espoused thinking and language aligned with the process and mind-set of the essence of design.

It’s not to say the story of GDS is without challenges or things that didn’t work well (no organisation ever simply starts a transformation process) nor is this a story wholly about design, but they have made significant savings, won national design awards and using Gov.uk is a great experience in comparison to previous Government online services. And, they’ve inspired others to follow suit on their design principles.

Looking forward on their plans they are working well beyond the basic transactional services on Gov.uk to linking up user journeys across departments to make services work for users. They have design and service patterns for use by the whole of Government and a scalable design system for ensuring all services are consistent in design and the efforts of design in Government are shared.

They are still on a journey, as transformation is never done, and in this space, design isn’t either. It never will be. The design discipline in Government is moving into a new space of perpetual beta, continuously improving and iterating services as an embedded function. It’s a very different design process to that of 20th century design disciplines but one departments and organisations across the public service are starting to adapt to.

These principles and stories have inspired others across Government and local government in the UK and globally to follow suit. For the rest of us who have been flying this flag for many years, it’s raised the profile of our work, with organisations across the public sector looking to finally start designing services that work for people.

Snook – Building Service Design in Government

On my watch, we’ve been running Snook for 8 years, working with big Government to small councils on improving services, but more widely, asking the question of how we build organisations that are user-centered and are structured with the right capabilities to do so. We have a distinct focus on building the capability of our clients as we deliver our work. It’s part of our ‘design on the inside’ programme where we work closely with organisations to train them in design whilst delivering live projects. What we believe is the most important element when embedding design is to ensure the focus on users is at the heart of the process. Service Design in Government isn’t just about the services, it’s about ensuring the organisation, the Government or the system has the capabilities to deliver in a user focused way.

Our design studio has worked on re-designing accident and emergency services with the NHS, new housing services to support vulnerable users, re-designing how education learner journeys work for the Government and researching how technology can support woman who face domestic violence for the charitable sector. Our work is channel agnostic to technology and digital however, we see it as a major opportunity to bring service design inside organisations.

In the past few years we’ve found an increase in the number of significant digital transformation programmes being started in the public sector that focus on technology and hardware before they think about the user experience. We’re on a mission to help change that and design a world that works better for people. We support all our clients to remember digital is the enabler in which to do so, not the answer.

With this, we use digital as our secret weapon to take organisations on a journey with us to re-think the user experience and services they offer for their users. We seek to find the most sensible place to embed design, and for us, this often lies with the digital teams, or I.T. It’s not to say that this is where design should be eternally embedded but the digital teams, or those tasked with digital transformation often have the remit to question and or re-design services so it makes a good vehicle for embedding design in most circumstances.

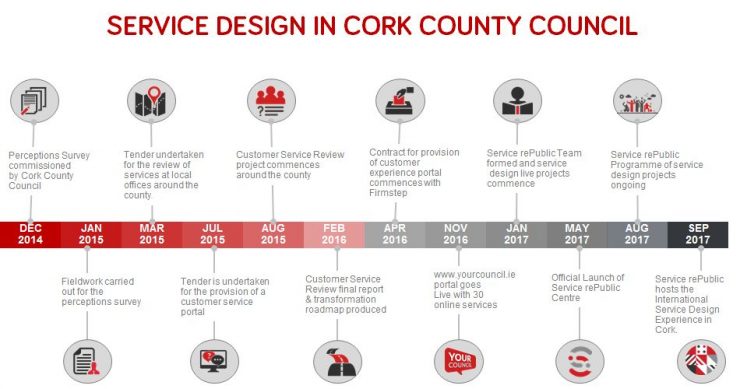

In 2017, we worked with Cork County Council to develop their focus on building a user-centered council. This initial engagement was a want by the leadership to build better services by design. We worked closely with the leadership team to identify an area of the business where they could embed design training and work across a series of live projects. We agreed to focus on the existing digital transformation effort in a new team called, ‘Customer service transformation’. Working collaboratively, we chose two projects; their community grant process and a housing service where elected councillors support residents with housing issues by making representations to the council.

When choosing a live project as a ‘trainer’ project we try to consider a series of elements to ensure it’s a good fit to trial using design to achieve change. In no particular order we considered;

Feasibility | Is it technically and operationally feasible?

Measurable impact | Can we achieve easy to measure impact in a short period?

Capability building | Will this support the building of design capabilities and skills?

Good news | Will it be a good news story to win hearts and minds in the council?

Building a movement | Will it build momentum and bring others on board across other departments?

Political persuasion | Does it fit a political stream of work we can attach it to?

User experience | Does it make an obvious improvement to the user experience?

We took the teams through a traditional agile process, teaching them user research and design skills across both projects. Our first project worked well, building basic design skills in researching with users, transforming these into user needs and prototyping new ways in which this service could be designed.

Our second project was with the housing department. Key to building this relationship was from our first project where we openly shared our project updates in learning lunches. These were low key, open sessions where people ate lunch whilst we showcased our raw work. This is a critical element of building design in-house helping to communicate and build relationships across departments. It showed people the inner workings of how design works.

The process was a simple agile process. We started with a discovery phase, where we spent time working with users of the service, both the public and service delivery teams to find out how they used the housing representation service. The service works by local councillors (called elected members) making a ‘representation’ to the council when a citizen has an issue with their home.

By shadowing staff, we found a process that was repetitive, largely paper based and involved data input across a range of system. On the user side, we found elected members were submitting information about residents that wasn’t being used like photos of the family, doctor’s notes, bank statements. The process end to end was costly to run and highly repetitive. There had been an initial fear to reach out and work in this way as user engagement isn’t common, but the process yielded brilliant insights that the service teams were completely unaware of.

After working through our insights of what we had learned, we undertook a series of co-design workshops with elected members, the housing department and front-line staff. We use these workshops to share the findings, produced journey maps of the customer experience and work together on re-designing opportunities. We printed off the process, form by form and walked the group around the room. It was at this point they realised how important language was, the service didn’t explain what it needed well and was difficult to understand.

Overall, we mapped out a new process involving less systems, clearer asks from elected members and digitising areas of it. We changed the design, took more of it online and re-wrote the questions in the forms for elected members. We then tested our re-designs with elected members and counsellors before going live. These iterations allowed a safe space for our designs to fail before being launched for real. Everything from the layout, to the instruction of the service and process in which to do this was tested by asking users to undertake tasks around making a representation.

Importantly this process was led by the Customer Service Transformation team. Our first project trained them in the basics of design, allowing them to lead the process.

The results, for a project delivered in six weeks were impactful.

There was an 86% decrease in time spent processing representations. The processing of documents by housing policy reduced from 15 minutes to less than 2 minutes per rep. In most cases elected members are submitting relevant documents directly, without processing needed. This means roughly a week of time saved per administrative staff member per month.

There was an instant response. There was a 100% decrease in time spent waiting for acknowledgement. The reps are now getting instant acknowledgements – they were previously waiting weeks despite having a KPI of 3 days. Nearly 75% of responses can be answered straightaway once they’re in the system.

A Dashboard is now always available which saves ½ day a month (6 days a year) in preparing a report for the Development Committee

There is a cost saving in postage of €1 per acknowledgment and response. This is a saving duplicated for the council and the elected members. We think this is roughly €12,000 a year in savings for the council and elected members.

But most importantly, this project was about winning hearts and minds.

“For me, the greatest part of the process had to be changing people’s mind-sets. Initially we weren’t given the go-ahead to work with elected members. After taking senior management in housing through the process, they got onboard, organised information and training workshops. I skipped back to the office”

ーKaren Fitzgerald, Customer Service Transformation Team

Cork continue on their journey to embed design. With 600 services, they’re working through the re-design of these to take them online and make sure they work for users.

Across all of Snook’s work when focusing on embedding design, we have to win the hearts and minds of people to want to work this way and see proven value in doing so. We usually face push back, risk-averse attitudes and ‘business as usual’ blockers, all which push back on design as a process for change. In this case of Cork, and many examples of our work, you’ll find design making an impact on the bottom line to save money and improve life experiences for people using services. This change takes time and is slow, because it’s a process of bringing people on the journey with you.

If you’re seeking a more transformative change, the other option is to consider a ‘Skunks work’ approach. We have experience of running innovative projects outside of Government and launching them to highlight new ways of thinking about how services can run in a completely transformed delivery model. In 2009, we built MyPolice, the UK’s first online feedback platform for the police to create new dialogue around service improvement, a world first for the criminal justice sector. We launched the new service in 2011, piloting with a police force Scotland. Through its use, we achieved service changes to local legislation due to feedback from citizens that wouldn’t have been captured through traditional means. Featured in the BBC, this product had an impact on how the police communicate with the public online, influencing the National Policing Improvement Agency’s social media policy and touring UK police forces to share the platform.

We advocate this as an approach to showcase social innovation or major transformation to a delivery model. However, it has it limitations in being fully adopted by the system but it shows a different way in which business as usual can be challenged.

Going beyond tools and processes

The most common ask of Snook is ‘can we build a toolkit’ that will help people understand Service Design. Whilst the answer is, yes we can if you really want to, the bigger answer is can we focus on delivering some measurable change? For us, this is much more about doing good work by design and ensuring the mind set and capabilities exist to use these types of tools to make services work better.

When we talk about a system having design capabilities or being designful, a good example is to take the developments currently in the Scottish public sector. Beyond GDS, Scotland has seen a steady development of adopting design methods across the Government over the past two years, something we’re proud to see given we started in Glasgow originally.

For a system of organisations to be designful, you need leadership, a capacity to think in scale, and couple these traits with building movements from the ground up.

An example of what Scotland is trialling is the Digital First Service Standard (DFSS). The Digital First Service Standard is a set of 22 criteria that all digital services developed by Scottish Central Government sector organisations and Scottish Government corporate services must meet. This includes services for users (for example submitting an application) or corporate services (for example checking your payslip online).The standard has 3 themes:

• user needs - focus on what your users want to do rather than the organisation’s objectives or the mechanics of delivering your service

• technology – how you’ve built your service

• business capability and capacity – having the right team with enough time to maintain the service

The standard aims to make sure that services in Scotland are continually improving and that users are always the focus. Most recently Snook has had a role in reviewing the implementation of DFSS for the Scottish Government. Whilst there is room to improve the implementation of a standard, the fact that organisations across the public sector are being assessed on their ability to design services that meet user needs, consider if they are accessible and have a ell thought through service design is a good start.

Standards like this are the kind of mature thinking in how design can scale that is now needed from Governments to mandate a minimum standard of what good design looks like. With standards we can work towards an assurance that design must be on the table as a serious approach to Government innovation. If we don’t align it politically or powerfully in ways like the DFSS, it becomes a ‘nice to have’ and not critical to business as usual. But design should be business as usual, it has the power to ensure that the services we offer to the public work for them.

Governments around the world are at a multitude of different stages when it comes to design. Worryingly, there are huge digital transformation programmes in existence not considering design or user needs at any stage within these. Find these programmes and support them to consider how design can make a difference to the work they are doing. This approach is very simple. Find out what people need, consider the user experience as a whole from what users see to how staff deliver the service and test the change you want to make. Then implement it, measure it and share your success. Then figure out how to do it again, and again and at scale. That’s your process to embed design in government.

Sarah Drummund

Sarah is the Co-founder and Managing Director of Snook whilst also being a serial idea generator. Over the last 7 years, she has initiated and delivered numerous projects including MyPolice, Dearest Scotland and CycleHack whilst also speaking and teaching worldwide from Oman to Australia. In 2016, she was named as one of GOOD Magazine's Top 100 influencers doing good in the world.